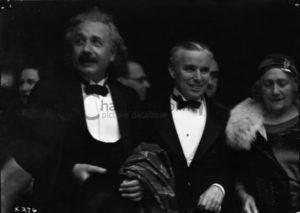

The Little Tramp considered “arguably the single most important artist produced by the cinema, certainly its most extraordinary performer and probably still its most universal icon”

By WILLIAM GODBY

Bosque Film Society Founding Board Member & Filmmaker in Residence

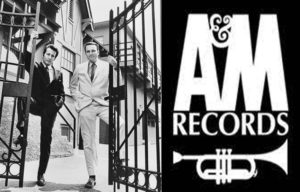

In the early 1980s, I started working at a production company, Jerry Kramer & Associates, located on the south end of A&M records which was originally the Charlie Chaplin Studios. We primarily did music videos, amongst them, Styx: Caught in the Act, The Pointer Sisters: Freedom, Michael Jackson: The Making of Thriller, Rod Stewart: Some Guys Have All the Luck, Madonna: Lucky Star, John Fogerty: Centerfield, Billy Crystal: You Look Marvelous, Bananarama: The Wild Life, Van Halen: Hot for Teacher and David Lee Roth: Just a Gigolo.

We shot a number of these at the Chaplin Stage on the A&M main lot. At the time, Wayne Isham, who went on to become a music video directorial icon, managed the stage. It was a grand time and ever so exciting. I’ve often thought how interesting it was to have walked the same ground that Chaplin graced.

The famous comedian built the Charlie Chaplin Studio after he signed with First National in 1917, his first independent production deal.

“At the end of the Mutual contract,” Chaplin later wrote, “I was anxious to get started with First National, but we had no studio. I decided to buy land in Hollywood and build one. The site was the corner of Sunset and La Brea and had a very fine ten-room house and five acres of lemon, orange and peach trees. We built a perfect unit, complete with developing plant, cutting room, and offices.”

The area purchased, extended from Sunset Blvd. south to De Longpre and bordered on the west by La Brea. The location was at that time a residential neighborhood, and area residents opposed Chaplin’s application for a building permit, however, the City Council voted 8–1 to approve his permit.

Chaplin built six English-style buildings, “arranged as to give the effect of a picturesque English village street,” to appease his neighbors. The layout was described by the LA Times in 2002 as a “fairy-tale cottage complex.” Another writer has described the style as “eccentric Peter Pan architecture.”

Construction of the studios was completed in 1919. Chaplin preserved a large existing residence on the northern end of the property, and planned to live there, but in fact, never did.

The “English cottages” along La Brea served as the facade for offices, a screening room, and a film laboratory. The grounds included stables, a swimming pool and tennis courts. The central part of the property, which was originally an orchard, became the back lot, where large outdoor sets were constructed.

The two large open-air stages used for filming were constructed on the southern end of the property, and the rest of the facility consisted of dressing rooms, a garage, a carpenter’s shed, and a film vault made up the rest of the five-acre property.

Chaplin built the English cottage-style studio in three months beginning in November 1917, at a reported cost of only $35,000, and opened in 1918.

Although he had a good chef installed in the big kitchen of his studio, he liked to be driven up La Brea to Hollywood Boulevard to lunch at Musso & Frank Grill, which was founded in 1919, the year production began at Chaplin Studios. He had his own booth there – right in front to the left as you enter – which is still known as “the Chaplin booth.

The restaurant is named for the original owners Joseph Musso and Frank Toulet. When it opened, the political and financial life of Los Angeles was centered in downtown LA, which was a difficult journey at that time. This made it possible for the restaurant to attract the more bohemian and intellectual clientele and has been called “the genesis of Hollywood.”

“We’d have lunch at Musso & Frank five days a week,” recalled the late composer David Raksin. “Everybody recognized him at Musso’s. He liked that but it wasn’t so important to him. He’d been famous since he was a boy.”

His first film under this new deal with First National was “A Dog’s Life” followed by “Shoulder Arms” which proved a veritable mirthquake at the box office and added enormously to Chaplin’s popularity. He followed “Shoulder Arms” with “Sunnyside” and “A Day’s Pleasure”, both released in 1919.

In April of that year, Chaplin joined with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith to found the United Artists Corporation. B.B. Hampton, in his “History of the Movies” says:

“The corporation was organized as a distributor, each of the artists retaining entire control of his or her respective producing activities, delivering to United Artists the completed pictures for distribution on the same general plan they would have followed with a distributing organization which they did not own. The stock of United Artists was divided equally among the founders. This arrangement introduced a new method into the industry.

“The corporation was organized as a distributor, each of the artists retaining entire control of his or her respective producing activities, delivering to United Artists the completed pictures for distribution on the same general plan they would have followed with a distributing organization which they did not own. The stock of United Artists was divided equally among the founders. This arrangement introduced a new method into the industry.

“Heretofore, producers and distributors had been the employers, paying salaries and sometimes a share of the profits to the stars. Under the United Artists system, the stars became their own employers. They had to do their own financing, but they received the producer profits that had formerly gone to their employers and each received his share of the profits of the distributing organization.”

However, before he could assume his responsibilities with United Artists, Chaplin had to complete his contract with First National. So early in 1921, he came out with a six-reel masterpiece: “The Kid”, in which he introduced to the screen one of the greatest child actors the world has ever known – Jackie Coogan.

Later in 1921, he released “The Idle Class”, in which he portrayed two characters, the Tramp and Edna Purviance’s wealthy husband.

Then, feeling the need for a complete rest from his motion picture activities, Chaplin sailed for Europe in September 1921. London, Paris, Berlin and other capitals on the continent gave him tumultuous receptions.

Chaplin returned to Hollywood to resume his picture work and start his active association with United Artists. Under his arrangement with U.A., Chaplin made eight pictures, each of feature length, in the following order: “A Woman of Paris” (1923), for the first he directed, in which he merely walked on for a few seconds as an unbilled and unrecognizable extra.

Followed by “The Gold Rush” (1925), and then “The Circus” (1928), for which he won an Academy Award in 1929. But as late as 1964, it seemed, this was a film he preferred to forget. The reason was not the film itself, but the deeply fraught circumstances surrounding its making.

The production of the film was the most difficult experience in Chaplin’s career. Numerous problems and delays occurred, including a studio fire, the death of Chaplin’s mother, as well as Chaplin’s bitter divorce from his second wife Lita Grey, and the Internal Revenue Services’s claim of owing back taxes, all of which culminated in filming being stalled for eight months. “The Circus” was the seventh-highest grossing silent film in cinema history taking in more than $3.8 million in 1928.

He made “City Lights” (1931), which proved to be the hardest and longest undertaking of Chaplin’s career. By the time it was completed he had spent two years and eight months on the work, with almost 190 days of actual shooting. By this time, sound film was firmly established.

This new revolution was a bigger challenge to Chaplin than to other silent stars. Chaplin boldly solved the problem by ignoring speech, and making “City Lights” in the way he had always worked before, as a silent film. However he astounded the press and the public by composing the entire score for “City Lights.”

He then made “Modern Times” (1936), a work on the social and economic problems of this new age. “The Great Dictator” (1940) was Chaplin’s first sound film.

Chaplin’s film advanced a stirring condemnation of Adolph Hitler and the rise of fascism in Europe. At the time of its first release, the United States was still formally at peace with Nazi Germany. Chaplin plays both leading roles: a ruthless fascist dictator and a persecuted Jewish barber, whose identities are switched by a series of events.

“The Great Dictator” was popular with audiences, becoming Chaplin’s most commercially successful film. Modern critics have praised it as a historically significant film, one of the greatest comedy films ever made and an important work of satire. Chaplin’s climactic monologue has frequently been listed by critics, historians and film buffs as perhaps the greatest monologue in film history, and possibly the most poignant recorded speech of the 20th century.

“Monsieur Verdoux” (1947) is an American black comedy directed by and starring Chaplin, who plays a bigamist wife killer inspired by serial killer Henri Désiré Landru, the Bluebeard of Gambais. The supporting cast includes Martha Raye, William Frawley and Marilyn Nash.

The idea was originally suggested by Orson Welles, as a project for a dramatized documentary on the career of the legendary French murderer Landru – who was executed in 1922, having murdered at least ten women, two dogs and one boy.

Chaplin was so intrigued by the idea that he paid Welles $5000 for it. The agreement was signed in 1941, but Chaplin took four more years to complete the script.

Chaplin was so intrigued by the idea that he paid Welles $5000 for it. The agreement was signed in 1941, but Chaplin took four more years to complete the script.

There were a number of ‘widow murder’ films produced in the 40’s. One in particular was “Shadow of a Doubt” (1943) starring Joseph Cotton and Teresa Brewer. But this was unlike any Chaplin film before, and it’s unapologetic dark tone, featuring as its protagonist a murderer who feels justified in committing his crimes, was poorly received in America when it first premiered.

When he is sentenced in the courtroom, rather than expressing remorse he takes the opportunity to say that the world encourages mass killers, and that compared to the makers of modern weapons he is but an amateur. Before being led from his cell to the guillotine, a journalist asks him for a story with a moral. He responds, “wars, conflict – it’s all business. One murder makes a villain, millions, and a hero. Numbers sanctify, my good fellow!”

At one press conference to promote the film, Chaplin invited questions from the press with the words “proceed with the butchering!”

Despite its poor commercial performance, it received excellent reviews from James Agee, Richard Coe and Evelyn Waugh. The film was nominated for the 1947 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. It also won the National Board of Review National Board award for Best Film and the Bodil Award for Best American Film.

Despite its poor commercial performance, it received excellent reviews from James Agee, Richard Coe and Evelyn Waugh. The film was nominated for the 1947 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. It also won the National Board of Review National Board award for Best Film and the Bodil Award for Best American Film.

In the decades since its release, “Monsieur Verdoux” has become more highly regarded. The Village Voice ranked the film at No. 112 in its Top 250 “Best Films of the Century” list in 1999, based on a poll of critics. The film was voted at No. 63 on the list of “100 Greatest Films” by the French magazine Cahiers du Cinema in 2008.

However, Chaplin’s popularity and public image had been irrevocably damaged by many scandals and political controversies before its release. In the late 1940s, America¹s Cold War paranoia reached its peak, and Chaplin, as a foreigner with liberal and humanist sympathies, was a prime target for political witch-hunters. This was the start of Chaplin’s last and unhappiest period in the United States.

In “Limelight” (1952), it’s not surprising he choose a subject that deliberately sought escape from disagreeable contemporary reality. He found it in a bittersweet nostalgia for the world of his youth – the world of the London music halls at the opening of the 20th century, where he had first discovered his genius as an entertainer.

In “Limelight” (1952), it’s not surprising he choose a subject that deliberately sought escape from disagreeable contemporary reality. He found it in a bittersweet nostalgia for the world of his youth – the world of the London music halls at the opening of the 20th century, where he had first discovered his genius as an entertainer.

With this strong underlay of nostalgia, Chaplin was at pains to evoke as accurately as possible the London he remembered from half a century before and it is clear from the preparatory notes for the film that the character of Calvero had a very similar childhood to Chaplin’s own.

“Limelight’s” story of a once famous music hall artist whom no one finds amusing any longer, may well have been similarly autobiographical as a sort of nightmare scenario.

Calvero, once a famous stage clown now a washed-up drunk, saves a young dancer, Thereza “Terry” Ambrose (Claire Bloom), from a suicide attempt. Nursing her back to health, Calvero helps Terry regain her self-esteem and resume her dancing career. In doing so, he regains his own self-confidence, but an attempt to make a comeback is met with failure.

Terry says she wants to marry Calvero despite their age difference, however, she has befriended Neville, played by Sydney Earl Chaplin, a young composer who Calvero believes would be better suited to her. In order to give them a chance, Calvero leaves home and becomes a street entertainer.

Terry, now starring in her own show, eventually finds him and persuades him to return to the stage for a benefit concert. Reunited with an old partner played by Buster Keaton, he gives a triumphant comeback performance. This was the only time Chaplin and Keaton appeared on screen together. In the film, Calvero suffers a heart attack following their routine, and dies in the wings while watching Terry, the second act on the bill, dance on stage.

Terry, now starring in her own show, eventually finds him and persuades him to return to the stage for a benefit concert. Reunited with an old partner played by Buster Keaton, he gives a triumphant comeback performance. This was the only time Chaplin and Keaton appeared on screen together. In the film, Calvero suffers a heart attack following their routine, and dies in the wings while watching Terry, the second act on the bill, dance on stage.

Upon the film’s release, the critical reception was divided; it was heavily boycotted in the United States and failed commercially. It was when on the boat travelling with his family to the London premiere of “Limelight” that Chaplin learned his re-entry pass to the United States had been rescinded based on allegations regarding his morals and politics.

Chaplin and his family settled at the Manoir de Ban in Corsier sur Vevey, Switzerland. His wife, Oona, returned to the states in 1953 to dispose of their assets.

Chaplin had been planning for that contingency for months, ensuring that his American wife was a cosigner on all of his bank and financial accounts in the U.S. Oona returned to the U.S. later that year alone and with a mission. She claimed she was returning to tend to her sick mother, but she was really returning to Beverly Hills to pack up the Chaplin’s home and settle their affairs.

Before selling their mansion, she took a shovel into the backyard. After Chaplin earned his first million dollars in America, he did something unusual with it. “He buried it in his yard under a tree, because he always wanted to know that he had that money. And when you come from the kind of poverty that Chaplin came from you can believe it,” says Jane Scovell, author of “Oona: Living in the Shadows.”

As part of her mission in the U.S., Chaplin instructed his wife to retrieve the buried cash, turn it into one thousand dollar bills and sew them into the lining of her mink coat, which she wore on her return flight across the Atlantic.

As part of her mission in the U.S., Chaplin instructed his wife to retrieve the buried cash, turn it into one thousand dollar bills and sew them into the lining of her mink coat, which she wore on her return flight across the Atlantic.

It’s a great story, but is it true? The cash-lined mink coat may be apocryphal, says Scovell, and we will never know for sure. But some of Chaplin’s closest friends and family members swore by it. Charlie and Oona would live the rest of their lives overseas in Switzerland as permanent exiles.

The studio was sold in 1953, to a New York real estate firm William Zeckendorf’s Webb & Knapp for $650,000. His longtime cameraman Rollie Totheroh collected as many negatives and prints as he could, and shipped them to Chaplin in Switzerland. Though priceless reels of outtakes were preserved in the vaults, the new owners discarded them, emptied out the prop room, and even destroyed the iconic giant wooden gears from “Modern Times.”

Despite the destruction of so much of Chaplin’s Hollywood history, the building itself was saved and leased out to a Chicago television production company. The lot became known as the Kling Studios, where “The Adventures of Superman” series was shot starring George Reeves.

Beginning in 1959, Red Skelton shot his television series at the facility, and in April 1960 Skelton purchased the studio. From behind a desk in the office once occupied by Chaplin, Skelton said.

“I’m not the head of the studio. I’ll be president and just own the joint…..Seriously, I couldn’t be a studio executive because I’m not qualified….I’ve got a nice enough racket trying to make people laugh and don’t intend to foul that up. And, besides, that’s harder than running a studio.”

“I’m not the head of the studio. I’ll be president and just own the joint…..Seriously, I couldn’t be a studio executive because I’m not qualified….I’ve got a nice enough racket trying to make people laugh and don’t intend to foul that up. And, besides, that’s harder than running a studio.”

Skelton purchased three large mobile units for taping color television shows, making a total investment estimated at $3.5 million. Skelton had a large “Skelton Studios” sign erected over the main gate on La Brea Avenue.

Skelton sold the studio to CBS in 1962, and CBS shot the “Perry Mason” television series there from 1962–1966.

In 1966, Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss purchased the studio from CBS to serve as headquarters for A&M Records. The company had grown from $500,000 in revenues in 1964 to $30 million in 1967. Alpert and Moss reportedly astonished the big network by having their bank deliver a cashier’s check for more than $1 million, the full amount.

A&M converted two of the old soundstages and Chaplin’s swimming pool into a recording studio. A 1968 profile on Alpert and Moss described their renovation of Chaplin’s old studios:

A&M converted two of the old soundstages and Chaplin’s swimming pool into a recording studio. A 1968 profile on Alpert and Moss described their renovation of Chaplin’s old studios:

“The old sound stages are in the process of being completely rebuilt into what must be the most luxurious and pleasant recording studios in the world. Chaplin’s cement footprints are one of the few reminders of the past.”

Within a decade of its inception, A&M became the world’s largest independent record company. Throughout the 1960’s and 1970’s, A&M had such acts as Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, Burt Bacharach, Sergio Mendes & Brasil ’66, Carpenters, Chris Montez, Captain and Tennille, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Quincy Jones, Liza Minnelli, Rita Coolidge, Wes Montgomery, Paul Desmond, Paul Williams, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs, Gene Clark and Billy Preston. During this time, A&M added several British artists to its roster, including Cat Stevens, Joe Cocker, Procol Harum, Humble Pie and Fairport Convention.

Other notable acts of the time included Nazareth, The Tubes, Styx, Supertramp, Joan Armatrading, Rick Wakeman, The Ozark Mountain Daredevils, Chuck Mangione, Squeeze and Peter Frampton.

A&M sustained its success during the 1980s with a roster of noted acts that included Janet Jackson, The Police, Sting, The Go-Go’s, Bryan Adams, Suzanne Vega, Oingo Boingo, The Human League, Joe Jackson, Soundgarden and Sheryl Crow. Their success is certainly reflected in the remarkable list of artists working for the label.

A&M sustained its success during the 1980s with a roster of noted acts that included Janet Jackson, The Police, Sting, The Go-Go’s, Bryan Adams, Suzanne Vega, Oingo Boingo, The Human League, Joe Jackson, Soundgarden and Sheryl Crow. Their success is certainly reflected in the remarkable list of artists working for the label.

During its time as A&M Records, the studio was host to multiple musicians recordings by many major artists such as Bruce Springsteen, the Rolling Stones, Joni Mitchell, Barbra Streisand, Art Garfunkel, Johnny Mathis, Carole King, Lionel Richie, Jackson Browne and the memorable “We Are the World” recording.

From the earliest days of sound film, music artists were recorded, from Al Jolson to Duke Ellington to Glenn Miller to Bill Haley and The Comets. Then, ideas for music television began in the 1960s. The Beatles used music videos to promote their records. Their 1964 film “A Hard Day’s Night” featured a performance of the song “Can’t Buy Me Love” which basically invented the music video.

In 1967, a Los Angeles company called Charlatan Productions began producing promotional films for rock groups, with a unique approach that involved interpreting individual songs by crafting original scripts and artistic scenarios to match. These short, song-length promo films were then distributed on videotape to TV stations around the country for artists such as Jimi Hendrix, The Animals, Steppenwolf, Aretha Franklin, Richie Havens and The Who.

At A&M, the first time the soundstage was seen on TV was in 1967 when the Tijuana Brass filmed part of its first television special there. In the early 1970s, the tours of George Harrison, Billy Preston, The Maharishi Orchestra and Joe Cocker were rehearsed on the soundstage.

The soundstage was used for remote recording of large group projects, these included: the quadrophonic version of Rick Wakeman’s album “Journey to the Center of the Earth.” Carpenters with the Overbudget Orchestra (Los Angeles Philharmonic) recording “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” in front of an audience of music journalists in 1977, and Herb Alpert and Hugh Masekela’s “The Main Event Live.”

The soundstage was used for remote recording of large group projects, these included: the quadrophonic version of Rick Wakeman’s album “Journey to the Center of the Earth.” Carpenters with the Overbudget Orchestra (Los Angeles Philharmonic) recording “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” in front of an audience of music journalists in 1977, and Herb Alpert and Hugh Masekela’s “The Main Event Live.”

In 1980, the soundstage was extensively revamped and rechristened the Chaplin Stage. There were changes to the roof, the floor was returned to its original concrete surface, a lighting rigging system was installed, bay patch, air conditioning plus the addition of dressing rooms, dining areas and recreation sectors.

Then the world changed with these words, “Ladies and gentlemen, rock and roll” as MTV premiered on Saturday, August 1, 1981. This had a huge impact on the media world in Los Angeles, creating a billion dollar industry overnight.

Among the music videos shot on the Chaplin Stage included: Carpenters “Close to You”, The Police “Every Breath You Take”, Jeff Beck “Ambitious”, Michael Jackson “Liberian Girl”, Vital Signs “The Boys and Girls Are Doing It” and Weird Al Yankovic’s “You Don’t Love Me Anymore.”

An equally if not more important date in the history of MTV occured on March 1, 1982. That’s when the then-struggling music video network launched the ad campaign that saved the day: “I Want My MTV!” The slogan was the genius of legendary Advertising Hall of Famer George Lois. Famous for his Esquire magazine covers and major ad campaigns of the 1960s, Lois was tapped to come up with something that would help sell MTV to the cable operators across America.

What would really sell the campaign, however, was the delivery: MTV exec Les Garland cajoled his friend Mick Jagger to shout the line into a camera. Once Jagger agreed to do it, David Bowie and Pete Townshend were persuaded to film spots as well. After that, getting new stars to join in snowballed into the famous “I Want My MTV!” commercials. The spots were a hit with cable providers, and subscriptions soared.

MTV was a driving force that catapulted music videos to a mainstream audience, turning music videos into an art form as well as a marketing machine that became beneficial to the record labels, recording studios and artists.

This had a huge impact on the media world in Los Angeles, creating a billion dollar industry overnight, as companies began creating music videos. This in turn influenced the ‘look’ of American film in the decades that followed. It seems that we did want our MTV!

In February 1969, the old Chaplin Studios were designated as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument. At the time, Carl Dentzel, the President of the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board, said the property was one of the few locations from old Hollywood that retained a complete early-day production layout. Dentzel also noted, “His studio was one of the first to be established here and by some quirk of fate, continuity from the movies’ earliest times to today’s television and recordings demands has persevered.” The studio was only the second entertainment related building to receive the Historic-Cultural Monument designation] after Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

Puppeteer Jim Henson had built a dynasty creating a cast of characters beloved by generations until his untimely death at the age of 53 in 1989. In February 2000, his children purchased the studio to serve as the new home of The Jim Henson Company.

Puppeteer Jim Henson had built a dynasty creating a cast of characters beloved by generations until his untimely death at the age of 53 in 1989. In February 2000, his children purchased the studio to serve as the new home of The Jim Henson Company.

Lisa Henson thought that the buildings were a lovable hodge-podge of quirky unusual spaces and believed that it may not be a location typical for corporate offices but felt that it was the right location for the Muppets. Henson’s son, Brian Henson, said that Chaplin’s studio was the perfect home for the Henson’s brand of classy but eccentric entertainment.

Although the Muppets now belong to Disney, the studio currently holds the Henson Recording Studios and the Henson Soundstage as well as the corporate headquarters for the Jim Henson Company and Jim Henson Creature Shop, a special/visual effects company.

The statue atop the entrance serves as one of the few reminders of the man who built the studio 100 years ago. The legacy that he left in the entertainment world lives through his films and the small studio declared a historic monument. Not an ending but a perfect continuation, now memorialized as a 12-foot Kermit the Frog statue dressed as Chaplin’s character “The Tramp,” a fitting tribute to two legends of the entertainment industry.

Chaplin made two more film while living in Switzerland.

In “A King in New York” (1957), Chaplin was the first film-maker to dare to expose, through satire and ridicule, the paranoia and political intolerance which overtook the United States in the Cold War years of the 1940s and 50s. Chaplin himself had a bitter personal experience of the American malaise of that time.

To take up film making again, as an exile, was a challenging undertaking. He was now nearing 70. For almost forty years he had enjoyed the luxury of his own studio and a staff of regular employees, who understood his way of working. Now, he had to work with strangers, in costly and unfriendly rented studios. The film shows the strain.

To take up film making again, as an exile, was a challenging undertaking. He was now nearing 70. For almost forty years he had enjoyed the luxury of his own studio and a staff of regular employees, who understood his way of working. Now, he had to work with strangers, in costly and unfriendly rented studios. The film shows the strain.

In 1966, he produced his last picture, “A Countess from Hong Kong” for Universal Pictures, his only film in color, starring Sophia Loren and Marlon Brando. The film started as a project called “Stowaway in the 1930’s”, planned for Paulette Goddard. Chaplin appears briefly as a ship steward, Chaplin’s son Sydney once again has an important role, and three of Chaplin’s daughters have small parts in the film. The film was unsuccessful at the box office, but Petula Clark had one or two hit records with songs from the soundtrack music and the music continues to be very popular.

Chaplin did finally return to the U.S. in 1972 to accept an honorary Oscar for his role in “making motion pictures the art form of this century.” A&M had hoped to welcome him back with a ceremony, but instead he chose to avoid the attention and arranged to drive by the studio gates on a weekend. The 82-year-old received his award to a 12-minute standing ovation, the longest in Academy Awards history.

Chaplin died on Christmas day 1977, survived by eight children from his last marriage with Oona O’Neill, and one son from his short marriage to Lita Grey.

While he may be gone, Chaplin’s legacy lives on even today. Hollywood will never have another star like Charlie Chaplin. In 1998, the film critic Andrew Sarris called Chaplin “arguably the single most important artist produced by the cinema, certainly its most extraordinary performer and probably still its most universal icon.” He was a titan of the cinema, and a true hero to oppressed people everywhere. His influence is sorely missed.