Commentary by J MATT WALLACE

Bosque Film Society Founding Filmmaker-In-Residence

I remain unfazed.

That word choice may sound defiant to some. However, I’m pleased to confirm that isn’t the case. I am, in fact, unfazed, but it’s in a zen-like peace that relishes the reality that I still love to love the 1987 movie Ishtar.

That word choice may sound defiant to some. However, I’m pleased to confirm that isn’t the case. I am, in fact, unfazed, but it’s in a zen-like peace that relishes the reality that I still love to love the 1987 movie Ishtar.

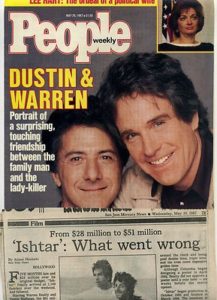

Why would I even reference the possibility of being fazed? Fazed by what? Well, it is a simple fact that Ishtar is not only one of my personal favorite movies, it also happens to be an all-time favorite for people who seem to love to hate it. “Hate” probably isn’t the correct word for most, though, but regardless of each person’s motivation, ridicule is the act. Am I overstating? I think not.

At some point in the late 1980s, it became obvious that things somehow evolved to the point where it was considered cool to “hate on” Ishtar. Whether or not you had actually seen the film was unimportant; it was just cool to make jokes about how awful the film was. Whatever ridicule-based phenomenon spread over popular U.S. culture back then has lingered. Matter of fact, that same vibe found a home amongst the founding members of the Bosque Film Society. While it is clearly in the name of good-natured ribbing, the jokes will never cease. I’m very OK with that. In 2021, I had the privilege of introducing the film Ishtar to our society as they sat, preparing to be shown the film in our beloved, beautiful Cliftex Theatre. I’ll spare you the specifics in this article, but if you don’t know about the small, historically significant Cliftex, look it up. It’s cool.

a foreign land while accommodating the whims of those same stars. The motivations that lead to Ishtar (in hindsight) make what happened with the film seem obvious. Beatty and Hoffman felt indebted to Elaine May for key work she had recently done on two incredibly successful films they had benefited from – Heaven Can Wait for Beatty and Tootsie for Hoffman. Fashioned after the classic “Road to…” films with Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, set in the Middle East, Elaine May throws in the twist that Hoffman is the cool character of the duo, not Beatty. At the time, Beatty was the coolest of the cool out of Hollywood. This fundamental schtick baked into the DNA of the film is what I enjoy immensely; I believe that this ongoing joke works well.

a foreign land while accommodating the whims of those same stars. The motivations that lead to Ishtar (in hindsight) make what happened with the film seem obvious. Beatty and Hoffman felt indebted to Elaine May for key work she had recently done on two incredibly successful films they had benefited from – Heaven Can Wait for Beatty and Tootsie for Hoffman. Fashioned after the classic “Road to…” films with Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, set in the Middle East, Elaine May throws in the twist that Hoffman is the cool character of the duo, not Beatty. At the time, Beatty was the coolest of the cool out of Hollywood. This fundamental schtick baked into the DNA of the film is what I enjoy immensely; I believe that this ongoing joke works well.

Beyond the ugly side of producing Ishtar, what ends up on the screen is not too far from the original silly, buddy film comedy vision. Within this romp, there are two aspects that are worth highlighting. First, Charles Grodin does a fantastic job in his role of a U.S. government operative within a volatile ridiculous geopolitical scenario. What parts of this film that work best are glued together with how he plays this part. Second, possibly the best part of the film are the songs these two bumbling song-writers have written and performed throughout the film. Paul Williams is quoted as “The real task was to write songs that were believably bad. It was one of the best jobs I’ve ever had in my life. I’ve never had more fun on a picture, but I’ve never worked harder.” His hard work and award-winning skill of writing excellent songs paid off with fantastically horrible songs that are true earworms. Williams crafted 11 of the tunes, and with the help of May, Beatty, Hoffman, and others, there are close to 30 different songs in this movie’s truly uniquely awful and wonderful soundtrack.

Over the years, others have emerged as fans of this film in the face of ridicule. At some point, I realized that I was not alone in my general admiration of the film. After a number of years of false starts, a fan-funded documentary film, Waiting for Ishtar: A Love Letter to the Most Misunderstood Movie of All Time was released in 2017. Indicative of the torment the film received over the years, The Far Side once captioned a clip of a video store’s entire stock made up of copies of Ishtar with “Hell’s Video Store.” Gary Larson later confessed that once he actually watched the film years later, he was stunned to realize it was actually funny and entertaining. Probably the best glimpse into the phenomenon is summed up in the director’s quote when May stated, “If all of the people who hate Ishtar had seen it, I would be a rich woman today.”

Over the years, others have emerged as fans of this film in the face of ridicule. At some point, I realized that I was not alone in my general admiration of the film. After a number of years of false starts, a fan-funded documentary film, Waiting for Ishtar: A Love Letter to the Most Misunderstood Movie of All Time was released in 2017. Indicative of the torment the film received over the years, The Far Side once captioned a clip of a video store’s entire stock made up of copies of Ishtar with “Hell’s Video Store.” Gary Larson later confessed that once he actually watched the film years later, he was stunned to realize it was actually funny and entertaining. Probably the best glimpse into the phenomenon is summed up in the director’s quote when May stated, “If all of the people who hate Ishtar had seen it, I would be a rich woman today.”

In the end, I will concede that Ishtar does not represent what makes a good movie; the number of ways it failed is not trivial. And yet, it happened; I’m grateful that it did. Watching Ishtar takes me to a fictional place, and tells a fantastic tale with actors I enjoy watching navigate the journey. The storyline of the film and the making of the film are both tragic and hilarious. The plot’s humor lampoons our ability to take ourselves way too seriously sometimes, while simultaneously documenting how absurd circumstances and oddly unaligned agendas can occasionally elevate lesser talented people into the spotlight. Likewise, in real life, there are systems in our world with inertia, power, and funding. Those systems produce things.