Emerging from Hollywood’s silent film era, Buster Keaton’s “THE GENERAL” somehow still seems relevant in modern times on the silver screen at the historic Cliftex Theatre in Clifton

By E. BRETT VOSS

Bosque Film Society Founder & Board President

“If you lose this war, don’t blame me.” “There were two loves in his life…his engine and Annabelle.”

Without question, Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin will forever be linked as the two ground breaking filmmakers of Hollywood’s silent era, both of whom navigated their way into continued success when “Talkies” took over the silver screen. But make no mistake about it, the connection between the two comic geniuses on the silver screen basically ends there.

As the Little Tramp and his many other iconic characters, Charlie Chaplin thrived as a theatrical master and relied on a theatre to make his mark. His movies play much, much better with an audience present creating a crescendo of reactions to his gags.

On the flip side, Buster Keaton stands out as the stoical hero delivering the comedy of resistance, the uncomplaining man of character who sees the world of order dissolving around him and endures it as best he can. And never was Keaton better in this role than in the 1926 slapstick Western action-comedy “THE GENERAL.”

On the flip side, Buster Keaton stands out as the stoical hero delivering the comedy of resistance, the uncomplaining man of character who sees the world of order dissolving around him and endures it as best he can. And never was Keaton better in this role than in the 1926 slapstick Western action-comedy “THE GENERAL.”

Without a doubt, while Chaplin remains revered, Keaton’s prominence has receded from where it stood half a century ago. Back in the day, if you were passionate about movies, you wore either the white rose of Keaton or the red rose of Chaplin – fiercely defending loyalty to your preference.

In Bernardo Bertolucci’s ode to cinema set to the backdrop of the Paris revolt in May 1968, “The Dreamers” features two student radicals – French and American – nearly come to blows over the relative merits of Charlie and Buster.

“Keaton is a real filmmaker. Chaplin, all he cares about is his own performance, his own ego!” “That’s bullshit!” “That’s not bullshit!”

Chaplin used staginess that transcended into sentimentality, while Keaton personified cinema – he moved like the motion pictures. Chaplin’s set pieces could easily fit onto a music hall stage – like the dance of the dinner rolls in “The Gold Rush” (1925) and the boxing match in “City Lights” (1931). Both were born imaginatively on the stage, and both could have been transposed there.

But Keaton’s set pieces could be made only with a camera. When he employs a vast and empty Yankee Stadium as a background for the private pantomime of a ballgame in “The Cameraman” (1928), or when he plays every part in a vaudeville theatre – including the testy society wives, the orchestra members, and the stagehands – in “The Play House” (1921), these things could not even be envisioned without the movies to imagine them in.

Directed by Keaton along with Clyde Bruckman, “The General” was released toward the end of the silent era and was not well received by critics and audiences, resulting in mediocre box office returns. Since being reevaluated, “The General” now ranks among the greatest American films ever made.

Directed by Keaton along with Clyde Bruckman, “The General” was released toward the end of the silent era and was not well received by critics and audiences, resulting in mediocre box office returns. Since being reevaluated, “The General” now ranks among the greatest American films ever made.

Inspired by the Great Locomotive Chase, a true story of an event that occurred during the American Civil War, The General was adapted from the 1889 memoir The Great Locomotive Chase by William Pittenger.

Keaton stars as Johnnie, who was rejected by the Confederate military, but not realizing the rejection was due to his crucial civilian role. The train engineer must single-handedly recapture his beloved locomotive after it is seized by Union spies and return it through enemy lines.

Make no mistake about it…Johnnie loves his train, The General, and his sweetheart Annabelle Lee, who thinks he was rejected to military service because he’s a coward. Union spies capture The General with Annabelle on board, and Johnnie must be heroic to rescue both his loves.

Critics believe Keaton’s greatest work was made in the five years between 1923 and 1928. “The General” in 1926, the first of Keaton’s features to enter the National Film Registry, was—surprisingly, to those who think of it as Keaton’s acknowledged masterpiece—a critical flop. A carefully plotted Civil War tale, more adventure story than comic spoof, The General shared the typical fate of many passion projects. At first, the film was a baffling failure, for which everyone blames the artist, and which does him or her immense professional damage. Then, the film gets rediscovered when the passion is all that’s evident and the financial perils of the project don’t matter anymore.

Nobody questioned Keaton’s decision to make it, since the movies he had made in the same system had all been profitable. But businessmen of the film industry have often compared the film to Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate.”

Nobody questioned Keaton’s decision to make it, since the movies he had made in the same system had all been profitable. But businessmen of the film industry have often compared the film to Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate.”

“The General was less a cause than a symptom of the end of a certain way of making movies. The independent production model that for 10 years had allowed Buster the freedom to make exactly the movies he wanted . . . was collapsing under its own weight.”

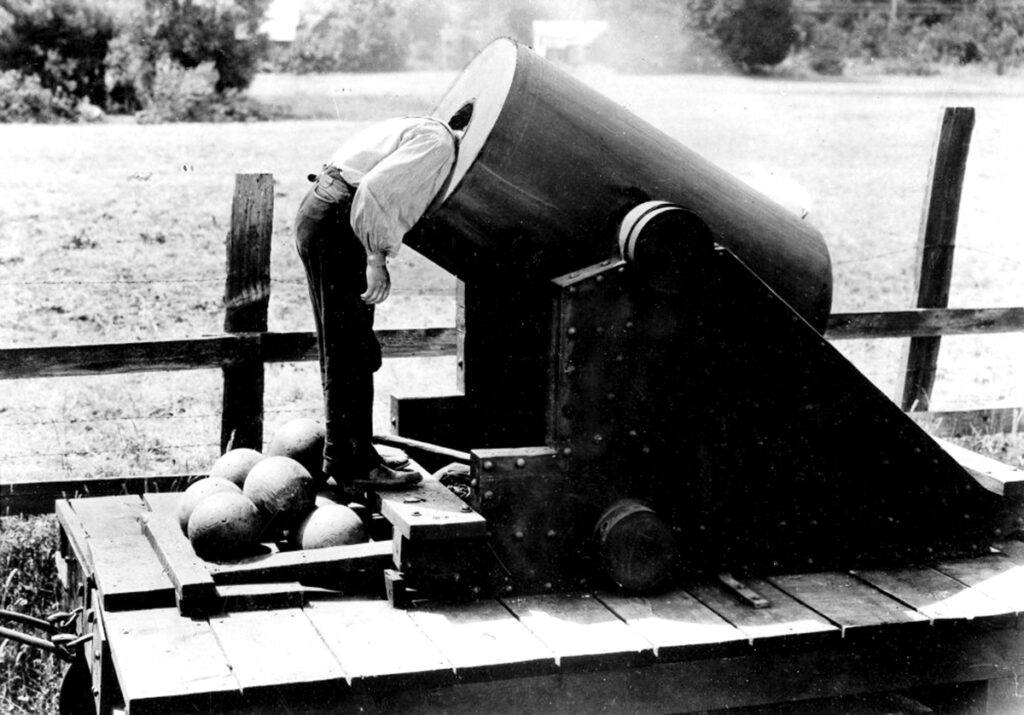

The thing that baffled its detractors and, at first, repelled audiences was the thing that now seems daring and audacious in retrospect – the seamless mixture of Keaton’s comedy with its soberly realistic rendering of the period. No American movie gives such a memorable evocation of the Civil War landscape, all smoky Southern mornings and austere encampments—a real triumph of art, like the image of a short-barreled cannon rolling alone on the railroad.

And then, there’s Keaton in the role of Johnnie. “Though there is a hurricane eternally raging about him, and though he is often fully caught up in it, Keaton’s constant drift is toward the quiet at the hurricane’s eye,” the critic Walter Kerr observed.

What remains most in one’s memory after an immersion in Keaton are the quiet, uncanny shots of him in seclusion, his sensitive face registering his own inwardness. Keaton seems to have been one of those comic geniuses who, when not working, never felt entirely alive.

In the early days of cinema, young comedians were being swept off the stage and into the movies. Keaton fell in with Joseph Schenck, then a novice movie producer, who paired him with Roscoe (Fatty) Arbuckle, matching a “natural” comedian with a technical one. With the partnership becoming an immediate success, the duo starting with the two-reel short “The Butcher Boy” (1917), before being briefly interrupted when Keaton was drafted to spend part of 1918 in France serving in World War I.

In the early days of cinema, young comedians were being swept off the stage and into the movies. Keaton fell in with Joseph Schenck, then a novice movie producer, who paired him with Roscoe (Fatty) Arbuckle, matching a “natural” comedian with a technical one. With the partnership becoming an immediate success, the duo starting with the two-reel short “The Butcher Boy” (1917), before being briefly interrupted when Keaton was drafted to spend part of 1918 in France serving in World War I.

In Keaton’s early entry into the movies, he seemed only really at home within the world of his own invention, mainly living for the choreography of movie moments, or “gags,” with scene, movement and story pressed together in one swoop of action.

When watching Keaton’s solo work today, viewers and critics alike tend to mull what exactly makes the films seem so modern?

Moments throughout “Sherlock Jr.” (1924) serves as prime examples as Keaton plays a dreamy projectionist who falls into his own films. With sequences like the one in which Keaton seems to step directly into the movie-house screen, then leaps from scene to scene within the projection in perfectly edited non sequiturs, Keaton achieves the Surrealist ambition to realize dreams as living action.

Consequently, in a modernistic way, Keaton’s movies very often are about the movies, which was a natural outgrowth of his single-minded absorption in his chosen medium.

“Though there is a hurricane eternally raging about him, and though he is often fully caught up in it, Keaton’s constant drift is toward the quiet at the hurricane’s eye,” the critic Walter Kerr wrote.

“Though there is a hurricane eternally raging about him, and though he is often fully caught up in it, Keaton’s constant drift is toward the quiet at the hurricane’s eye,” the critic Walter Kerr wrote.

Interestingly, Keaton’s most famous appearance late in his career was alongside Chaplin in 1952’s “Limelight.” Arguably Chaplin’s last interesting movie, the comic legends play two down-on-their-luck vaudevillians.

When watching a collection of Keaton films, his lasting impression remains the quiet, uncanny shots of him in seclusion, his sensitive face registering his own inwardness – justifying a reason to take a closer look at Keaton, even today.

Chaplin stands out as a theatrical master that needs a theatre to make his mark. His movies play much, much better with an audience present. Keaton can be a solitary entertainment, the chamber-music master of comedy, with the counterpoint clear and unmuddied by extraneous emotion.

But without a doubt, the most unforgettable thing about Buster Keaton will always be his deadpan face, definitely on display to full effect in “The General.” Even in the 1966 film “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum” made a year before his death, Keaton’s face was a beacon, not merely of endurance, but of a kind of lost American integrity, the integrity of the engineer, the artisan and the old-style vaudeville performer.

Considering the fact that The Cliftex Theatre ranks as the longest continuously operating movie house, showing motion pictures on the silver screen since 1916, it’s only fitting as the venue to once again watch the incomparable Buster Keaton in “The General.”